Container Pioneer: How Innovative Leadership Shaped the Future of Global Trade

Yesterday I had the opportunity to learn first hand about the Port of Savannah and container ship transportation. I posted about that experience in The Modern Container Port. That experience caused me to dig in and learn more about how the whole container shipping industry evolved. I learned that Malcolm McLean was the innovative, systems change leader who invented and patented containerized shipping. Over 90% of global shipping now happens using the TEU (Twenty Foot Equivalent Container Units) containers. That invention and standardization was said to have improved shipping efficiency by 25%. Now that’s innovation!

McLean’s invention of the shipping container and the semi trailers the containers can be mounted on offers a powerful leadership lesson in innovation and systems leadership by exemplifying how vision, boldness, and systemic thinking can revolutionize an entire industry. Here are some key takeaways:

- Challenging the Status Quo: McLean identified inefficiencies in traditional break-bulk cargo handling and questioned existing practices. Great leaders aren’t afraid to challenge conventional methods and look for transformative solutions.

- Innovative Thinking for Large-Scale Impact: His idea to standardize cargo into containers was groundbreaking, demonstrating the importance of thinking big and considering how innovations can positively impact multiple facets of an industry.

- Commitment to Vision: McLean persisted despite initial resistance, showing that dedication and resilience are essential for turning innovative ideas into reality.

- Systemic Change and Leadership: His invention didn’t just improve efficiency; it redefined global trade logistics, illustrating how visionary leadership can effect widespread change through strategic innovation.

- Embracing Risk and Learning: McLean’s journey underscores the importance of taking calculated risks and being open to learning from failures, which are vital traits for innovative leaders.

Malcolm McLean’s story teaches us that effective leadership involves recognizing opportunities for innovation, daring to challenge existing paradigms, use systems thinking to disrupt markets, and having the perseverance to implement game-changing solutions that benefit industries and communities worldwide.

The Modern Container Port

I had an incredible experience today! I had a private tour by Captain Dan of the Port of Savannah in Savannah, Georgia. The Port of Savannah is the largest single container terminal in the Western Hemisphere. Container shipping is measured in TEUs (Twenty Foot Equivalent Container Units). Last year the Port of Savannah saw 5.25 million TEUs moved. I had been really wanting to learn about this incredible port and my dream came true with Captain Dan.

I’m going to let my photos do some talking here:

As one of the nation’s busiest ports, Savannah handles a significant volume of containerized cargo, thanks to its deepwater ports, state-of-the-art terminals, and efficient infrastructure. The port’s strategic location, coupled with its expansive railroad and highway connections, makes it an ideal hub for distributing goods across the Southeast and beyond. Major shipping lines regularly call at Savannah, facilitating international trade, particularly with Asia, Europe, and Central America. The port’s ongoing investments in modernizing facilities and expanding capacity reflect its commitment to maintaining its competitive edge, supporting regional economic growth, and enabling seamless global commerce.

I made the comment to Captain Dan that I was excited for this learning today because every year I try to learn something new about the Savannah/Tybee Island, Georgia area when I am here. He said he was the same way in that he made sure he was learning and getting new certifications and qualifications each year. He then quoted Dave Ramsey as saying, “We should learn something new today and dispel the fear of what we don’t understand.” This conversation was a good reminder of how important it is for us to stay curious and keep learning. What new things do you want to learn?

Why Wait?

I had a person yesterday morning say to me, “Boy, you sure don’t wait around!” This was in response to a conversation we were having that resulted in needing to ask another person a question and I just picked up my phone and called that person and put them on speaker. One thing I have learned over the years is the more I do things immediately, like making a call, the better things turn out. This is especially true with difficult conversations. My theory is, why wait?

In yesterday’s context the conversation was not a difficult one, just one that it sped things up to get the answer right then. I hate it in meetings when someone says, “Let’s take that offline.” No! Let’s get it handled right now. Basically, I am a “get things done” person. Those that know me know I will a lot of times say, “Let’s do something, even if it’s wrong.” Now I know that is not always the best approach, but think about all the times when you or a group kept talking about something and the window of opportunity closed and passed you by.

A lot of times we put off difficult conversations, but what I have found is that is best just to get them done. I say this because many times the conversations don’t turn out to be as bad as we think they will be. Therefore, it is best to get those conversations done and over with so they are not hanging over our heads and stressing us out. This is what Brian Tracy called “eating the frog.” Tracy taught us that when we have a big challenge to go ahead and get it out of the way first. In other words, don’t wait around; get it done.

Leading Like Dolphins

Yesterday morning I had the opportunity to watch a pod of dolphins playing and fishing right next to the pier on Tybee Island. As I watched and admired I was reminded how dolphins are the perfect balance of intelligence, compassion, and adaptability that define inspiring and effective leadership. Dolphins can serve as a powerful metaphor for leadership because they also exemplify qualities such as intelligence, teamwork, communication, and resilience.

Just as dolphins work together seamlessly in pods, effective leaders foster collaboration and unity within their teams. The dolphins playful curiosity and adaptability symbolize the importance of innovation and open-mindedness in leadership.

Dolphins are highly adaptable in diverse environments and can quickly adjust their strategies. The best leaders are flexible and creative problem-solvers, especially when it comes to navigating changing circumstances. As effective communicators, dolphins use a complex system of sounds and gestures to communicate with each other. As leaders we must foster open, transparent communication within their teams to ensure everyone is aligned and engaged.

Embracing qualities like playfulness and adaptability—much like dolphins—can significantly enhance leadership effectiveness. By fostering a positive environment and valuing strong communication, we can build resilient and motivated teams capable of overcoming any challenge.

Inner Freedom: Shaping How We Perceive and Respond to the World

I wrote about freedom back in 2020 in Remember, Freedom Is Yours Until You Give It Up. Reading in G. K. Chesterton’s Autobiography this morning prompted me to reread my post and realize my words I wrote then are still relevant today. Then I read this from G. K. Chesterton this morning, “From the first vaguely, and of late more and more clearly, I have felt that the world is conceiving liberty as something that merely works outwards. And I have always conceived it as something that works inwards.” This caused me to think deeply about what Chesterton meant by this.

I believe Chesterton was highlighting a distinction between the superficial and deeper understandings of liberty. When he says that the world often sees liberty as something that “merely works outwards,” he’s referring to the common view that freedom is about external circumstances—such as political rights, legal freedoms, or outward expressions.

However, I’ve found from studying Chesterton that he believed that true liberty is more inward and spiritual. He conceived it as an internal state—a form of self-mastery or inner freedom—that influences how we think, feel, and make choices. In essence, he was emphasizing that genuine liberty begins within the individual, shaping how we perceive and respond to the world, rather than just external conditions or constraints.

It always amazes me how a couple of sentences from a great author can make a person think. Chesterton’s saying, “From the first vaguely, and of late more and more clearly, I have felt that the world is conceiving liberty as something that merely works outwards. And I have always conceived it as something that works inwards” did that for me. His perspective encourages looking inward for freedom—cultivating inner independence and moral integrity—rather than solely focusing on external rights or societal structures.

Soaring High: Embracing the Learning Journey to Master Kite Flying and Leadership

I love watching people flying kites on the beach. In particular, I love watching children having fun flying kites on the beach. Yesterday morning I looked on while a youngster had the productive struggle of learning to fly a kite. And, by the way, I am a big believer in productive struggle as a best practice for teaching and learning. The child’s parents were helping, but I’m pretty sure they were learning to fly a kite for the first time too. Of course, all of this led to an analogy.

Just like a child learning to fly a kite, someone stepping into a leadership role often faces uncertainty and challenges initially. The child’s productive struggle—feeling the wind, adjusting the tail, experimenting with different angles—mirrors how a new leader learns through trial and error, gaining confidence and skill over time. And a cool thing happened; all of the sudden the kite caught the wind just right and it was game on. Even from a distance I could tell the young person had that “Oh crap” moment of “It’s flying, now what do I do?” It was so much fun and so inspiring to watch. By the way: I’m pretty sure Orville Wright had that same “Oh Crap! I’m flying! Now what do I do?” moment on December 17, 1903!

Both situations emphasize the importance of patience, perseverance, and a willingness to learn. The child never once gave up when the kite dipped or struggled against the wind; instead, I could tell they were learning to read the conditions and adapt. Similarly, a leader who admits they don’t have all the answers (practices being vulnerable) and remains open to growth can develop resilience, wisdom, and better decision-making skills.

In essence, this analogy reminds us that embracing the discomfort of not knowing everything upfront allowed both the child and us as leaders, to develop competence, confidence, and a deeper understanding of our environments. It’s about valuing the journey of learning and trusting that with effort and openness, mastery—whether in flying a kite or leading others—is achievable.

Reconnecting

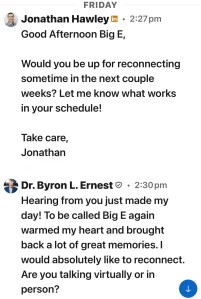

Yesterday I got to do something that I believe every educator reading this post would say are some of the greatest moments as an educator: reconnecting with former students. On Friday of last week I got this message from Jonathan Hawley:

Good Afternoon Big E,

Would you be up for reconnecting sometime in the next couple weeks? Let me know what works in your schedule!

Take care,

Jonathan

That message absolutely made my day. One, because it has been a lot of years since someone called me, “Big E.” Back in the day that was what all my students called me. Of course, I responded immediately that I would love to reconnect (see the featured photo).

Yesterday, we spent nearly an hour reconnecting. It was like no time had passed at all since we were last together. The point of this post is not to retell those stories, because those would be out of context for you. My point is however to reinforce how important building relationships is, particularly for teachers with students, and the tremendous value in reconnecting that Jonathan so wonderfully modeled for me.

As an agriculture science teacher I had the opportunity to really get to know our students and their families. In Jonathan’s case I was able to travel overseas with him not once, but twice. Those relationships then transform into incredible learning. It was so great to hear Jonathan share things he uses yet today that he learned from those experiences.

This reminder of the importance of relationships goes beyond education to all organizations and leadership. I am a believer in taking relationships beyond the surface level. Relationships matter. Relationship that go beyond surface level are built on a solid foundation of trust and mutual understanding. Those deeper connections provide emotional fulfillment and satisfaction that transcends mere service or reciprocity.

Reconnecting with people from our past can be incredibly fulfilling and wonderful because it allows us to rediscover shared memories, regain a sense of belonging, and see how both we and our relationships have evolved over time. It was so awesome to reconnect and get to know the Jonathan of today – a father of three and successful leader and professional.

Moments like yesterday bring an inspiring reminder of the bonds and experiences that shaped us, fostering feelings of nostalgia, gratitude, and renewed connection. This reconnection also offered new perspectives and insights, enriching our understanding of ourselves. For example, it inspired this post and me to think deeply about others I need to reconnect with. How about you? Is there someone you need to reconnect with?

Balancing Ambition and Realism: Strategies for Sustainable Success

The other night I got caught up watching the 2010 classic The A-Team movie. If you haven’t seen it, it is awesome. The line that always causes me to pause and reflect is when Colonel John ‘Hannibal’ Smith, played by Liam Neeson, says, “Overkill is underrated.” As a person who often gets credited for turning ordinary things into big deals or events, I love the comment. Now, I get the fact that in the movie as Hannibal makes the comment that he is dumping an entire box of fireworks into a distraction that probably only needs a couple, but stay with me for the analogy.

Sometimes, going above and beyond or exceeding expectations can be more effective than just meeting minimum standards. In leadership, this reminds us the value of thoroughness, extra effort, and attention to detail—showing commitment and inspiring confidence. It encourages us to deliver more than what’s necessary to achieve excellence and foster trust. I like going into this mode on projects because of the shock and awe effect of it. I’m reminded of going big or going home!

While the idea of “overkill” can often lead to high-quality results and demonstrate dedication, I would be remiss if I didn’t recognize there are situations where it might not be the best approach. There have been times where I have caught myself going into “overkill” mode and was in jeopardy of overextending efforts or using excessive resources on a task that doesn’t require it can lead to inefficiency and waste.

While ambitious dedication is admirable, and I believe a good thing, it’s important to balance effort with practicality and context to ensure that striving for excellence remains sustainable and appropriate.

Leading a Stronger Team: Embracing Diversity Like a Vibrant, Harmonious Beach Scene

Yesterday was an absolutely beautiful day on Tybee Island. Sunny, no wind, and 70°F (degree Fahrenheit) or 21°C (degree Celsius). The beach was full all day and it was fun to watch people come and go. Some were coming as individuals, some as couples, others as groups of friends, and others as families. Some came with fishing gear, others with beach gear to camp out for the day, others with games and kites, and some just to take a walk. Many had just stopped to walk out and stick their toes in the Atlantic Ocean. Then at the end of the day, as the sun was going down, people in bathing suites were leaving meeting others just arriving in sweatshirts and coats.

As I witnessed all this it got me thinking about how we all experience nature in different ways. Some of how we show up is dictated by how we like to show up at the beach, but for others showing up is dictated by the group they are a part of. This made me reflect on how our workplaces and organizations are not much different. Do we have a culture that invites belonging and differences in how we show up?

Think about it. Just as each person brings their unique mindset and goals to the beach, team members come with their own backgrounds, motivations, and expectations. Our teams show up based on the makeup of the team. As leaders it is important for us to recognize and respect these differences, allowing us to create an inclusive environment where everyone belongs and feels valued and understood.

Some team members may seek collaboration and connection, much like those enjoying socializing at the beach. Others might prefer solitude or focused work, similar to someone peacefully reading alone. Some may be adventurous and eager to try new things, akin to exploring tide pools or surfing.

By understanding these varied ways of showing up, we can practice adaptive leadership by providing support, setting appropriate challenges, and fostering a culture that appreciates diversity. This ensures all voices are heard and empowered, leading to a more dynamic, resilient, and cohesive group—just like a lively, harmonious beach scene where everyone’s presence contributes to the overall experience.

Reflections of Success: How Mentors Help Mentees Recognize and Leverage Their Strengths

This morning as I was watching the sun come up and how the ocean was serving as a mirror of the sun reflecting its brightness and beauty, I was reminded how important it is for us, as leaders to reflect those we serve strengths back to them. As I worked with a group of mentor teachers this past week, we discussed how being a great mentor and leader involved reflecting strengths back to mentees. Just what does that mean, though?

It means the mentor is aware, recognizes and reinforces the individual qualities, skills, and potential that each mentee possesses. Highlighting these strengths, by reflecting them back, the mentor helps the mentee see their own capabilities more clearly, boosting their confidence and encouraging further growth. This acknowledgment not only validates the mentee’s efforts but also empowers them to leverage their strengths in future challenges, fostering self-awareness and resilience along their development journey.

So, as we reflect on our own personal and professional lives, let’s not forget to turn the mirror around and reflect the strengths of those we serve back to them.

leave a comment